The Hardening of Policies between the UK and France: Consequences of the New Agreement

April 2023, Calais, France, Words by: Coline Jeancourt-Galignani

Changing asylum law to change the situation at the border:

Earlier this month, the UK drafted a bill to make asylum applications from people who enter the country illegally inadmissible. This bill is an apparent attack on the right to asylum, and many associations have taken up this issue. Collective Aid joins these denunciations. The bill also marks a change in the anti-migration strategy built by the British government for years. So far, the Kingdom, to turn back people at the border, has worked on hardening the border controls in France. In addition, they aimed to avoid people crossing the Channel thanks to military forces. The government directly tackles the right to asylum through the new bill carried by the Ministry of Interior, Mme Suella Braverman.

Yet, the executive's will remains to decrease the number of people crossing the border: by announcing that the asylum application will be inadmissible, the government expects to discourage the crossings. The bill has thus directly impacted hundreds of people stuck at the border in Calais.

Status quo for Channel crossings

It is necessary first to underline that no attempt to harden the border has ever been followed by a reduction in the number of crossings, at most a change in the way people cross. A report published by the French Human Rights Council (CNCDH) in 2021 revealed that £150 million had been used in border hardening between 2016 and 2021. Border patrols, video monitoring, barbed wire, and hostile architecture have multiplied in Calais, creating a city of violence where the number of deaths while crossing does not stop increasing. And despite these investments, while in 2015, 32,733 asylum applications were lodged by people arriving in the UK, there were 74,751 in 2022. Thus, there is no correlation between the increase in border strictness and the number of people actually arriving to ask for asylum.

In our particular case, since border controls are not directly impacted, crossings will remain the same in number and substance. The more vicious repression will occur once they arrive in the UK after applying for asylum. From this point of view, therefore, Calais will a priori remain a crossing point, a place of transit.

From a holding point to an open-air pre-detention area?

Currently, Calais is considered a step in the movement of people stuck in the city. They share the will to reach England and get there their refugee status. That is why French legal experts on human rights have depicted Calais as a "holding area." But the bill brought to the fore by the British government changed this situation altogether. Indeed, the government promises that people arriving illegally on the territory will be brought into a detention facility for up to 28 days before being sent to their country of origin or another "safe country," such as Rwanda or Albania. The bill will then make Calais the last step before the detention for those who cannot cross illegally. So from this point of view, Calais won't be a holding point anymore but an open-air temporary detention point.

How the "securitisation" of borders puts people at risk:

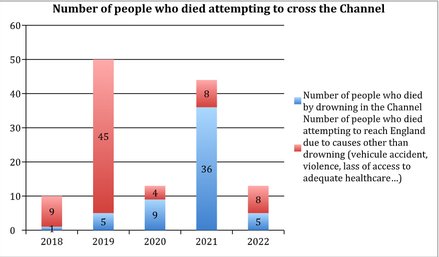

In 2022, almost 46,000 people attempted to cross the Channel in small boats. The fortification policy of the French coastline can explain this exponential growth. This exponential growth is defined by the policy of fortifying the French coast. Indeed, the investments made by the French and British governments to prevent crossings have not ceased to increase since 2015 (360 million euros have been given to France from the UK between 2014 and 2022 to fortify the borders). In government words, these investments are supposed to "secure" the border. But in reality, they force people to take other and more dangerous routes further down the coast and take on more risks. Indeed, most securitising resources have focused on patrolling the highways, the Euro tunnel, and the Calais port. It has become almost impossible for people on the move to cross in trucks or ferries. However, people keep trying. The coastline has become virtually the only possible way out. It is, however, much more deadly. Since signing the Le Touquet agreements in 2003, more than 300 people have died in the Channel. More than 205 of them died from 2014 to 2022. By increasing surveillance, the authorities are contributing to an increase in the number of deaths in the Channel.

A cycle that must be broken:

Since 2003, twenty agreements have been signed between France and England. Each one marks the failure of its predecessors, but despite this evidence, the public policy continues to focus on the hardening of the border. As governments have recently affirmed again their willingness to continue down this path, it is to be expected that increasingly perilous routes will be taken. First, the surveillance of beaches and roads tends to widen the area of departure by sea to England. While there is about 35km of ocean to cross between Calais and the English coast, more and more people are leaving beaches that are sometimes more than 80km away from the English coast. The sailing conditions in the English Channel are harsh, and the wind and the sea currents can force boats to travel sometimes twice as far to reach their destination. As a result, more and more boats will travel more than a hundred kilometers in the hope of reaching the UK, making the chances of arriving safely even slimmer. The last ten years can only testify to the fact that this cycle will not stop: the more the authorities invest in preventing crossings, the more dangerous they will become, and the more people will die at sea. These criminal policies need to stop.